Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

I had thought only slavery dreadful, but the state of a free negro appeared to me now equally so at least, and in some respects even worse, for they live in constant alarm for their liberty.

On this site, explore the lives of the historical free Black community of Natchez Mississippi. The stories contained here emphasize the perilous and uncertain space between freedom and enslavement this small but highly significant community occupied. It is hoped they will serve to educate, aid further research, and broaden the wider historical understanding of Natchez during this time.

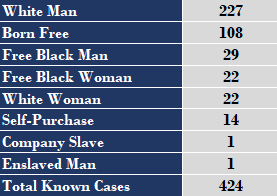

Free Black people in Natchez occupied a tenuous space between freedom and enslavement during the period of 1779 under Spanish governance through the American acquisition in 1795 and continuing until the Civil War in 1865. They were not legally owned like the majority of African Americans living in the US, but they did not have unlimited enjoyment of their liberty. In myriad ways, this group of people who have been described as living “ambiguous lives,” “in the margins,” or “in shadow” and whose freedom was often contested, had to exert considerable effort to remain free.[1] Mississippi legislators exerted great effort to control the growth of their numbers. In 1860, on the eve of the Civil War, Mississippi had one of the largest enslaved populations in the United States, at 436,631, but only 775 free people of color, the smallest population of all southern states. Natchez distinguished itself within Mississippi for having the largest community of free people of color, but it was still a small number: only 225 free Black people resided in Natchez and Adams County compared to 14,292 enslaved African Americans.[2] In relation to New Orleans, where the free Black population numbered in the thousands during most of the time period under consideration, Natchez’s community was tiny indeed.

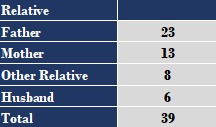

The people themselves embodied a diversity of origins and identities. A few were born in Africa. One man, for example, found himself enslaved on the battlefield in West Africa and sold into slavery in Natchez. He claimed royal ancestry and found supporters willing to aid him in his bid for freedom and return to Africa, along with his American-born wife.[3] Some purchased their family members out of slavery and manumitted them. One woman bought her sister and niece out of slavery, but due to strict manumission laws, had to continue to legally own them for a time before their eventual emancipation. Others were freed as a result of performing a service such as nursing an enslaver through a sickness, saving a home from burning in a fire, or fighting in a war. A number of women were freed as a consequence of having been sexually involved with white men, some having had children with them. Others moved into the area, some looking for opportunity, some following enslaved family members, and some were kidnapped and forcibly brought. There were a great many people who had to fight to prove their freedom through Natchez’s courts. A large segment of the population was born free, without any experience or memories of enslavement.[4]

Freedom for people of African ancestry was not necessarily a permanent condition, but one marked instead with permeable boundaries that engendered a tenuous and unstable state of purgatory between enslavement and freedom. As several Natchez free people of color showed through their lived experiences, one could be born into slavery, become manumitted, and even be re-enslaved for failure to pay taxes or being accused of a crime and imprisoned, all in one lifetime. Additionally, there were multiple restrictions placed upon them dictating the conditions of their lives. For example, they could not vote, hold office, testify in criminal court against whites, or serve on juries. Certain occupations were closed off to them and there were many discriminatory indignities they experienced. There were certain events like real or reputed slave rebellions that would increase white hostility and repression towards them. This type of episode occurred in 1841, a period of time that free Black diarist William Johnson termed “the Inquisition,” and free Black people were forced to come before the Police Board and certify their good characters. Some were ordered out of Natchez. Freedom was thus often challenging to retain.

In spite of these significant obstacles to the full actualization of their liberty, though, free Black people devised ways to protect themselves and their families by using the courts, finding allies, developing friendships, and accumulating property. Their lives demonstrated great feats of love for their families and friends, care for their communities, and a determination not only to survive, but to thrive in freedom. In short, they strove to live and prosper under uncertain conditions.

[1] Scholarship that has been generated regarding the ambiguity of the status of free Black people is quite uniform. For a short listing of some prominent works that speak to this see Adele Logan Alexander, Ambiguous Lives: Free Women of Color in Rural Georgia,1789-1879 (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1991); Ira Berlin, Slaves without Masters: The Free Negro in the Antebellum South (New York: Vintage Books, 1971); and Marina Wikramamayake, A World of Shadow: The Free Blacks in Antebellum South Carolina (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1973). For more references to free Blacks in general, consult the “Resources” tab on this website.

The scholarship on Natchez’s free Black community essentially began with Edwin Adams Davis and William Ransom Hogan published in 1954, entitled The Barber of Natchez (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1954). Although they used his diary, which he kept from 1835-1851 more as a springboard from which to discuss white Natchez, they devote some time to the free community of color besides the Johnsons. See Edwin Adams Davis and William Ransom Hogan, William Johnson’s Natchez: The Antebellum Diary of a Free Negro (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1951). Virginia Meacham Gould importantly published a collection of letters and other writings from some of the women in Johnson’s family in her Chained to the Rock of Adversity: To be Free, Black, & Female in the Old South (Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 1998). Others who have written on free Black people in Natchez—although not a wholly exhaustive list—includes: Ronald L. F. Davis, The Black Experience in Natchez, 1720-1880 (Denver: National Park Service, 1999); Joyce Broussard, Stepping Lively in Place: The Not-Married, Free Women of Civil War–Era Natchez, Mississippi (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2016) and Kimberly M. Welch, Black Litigants in the Antebellum American South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018).

[2] Historical Census Browser. Retrieved [July 10, 2010], from the University of Virginia, Geospatial and Statistical Data Center: http://fisher.lib.virginia.edu/collections/stats/histcensus/index.html.

[3] Terry Alford, Prince Among Slaves: The True Story of an African Prince Sold into Slavery in the American South (30th Anniversary Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

[4] Nik Ribianszky, Generations of Freedom: Gender, Movement, and Violence in Natchez, 1779-1865 (University of Georgia Press, 2021).

In Generations of Freedom, Nik Ribianszky employs the lenses of gender and violence to examine family, community, and the tenacious struggles by which free blacks claimed and maintained their freedom under shifting international governance from Spanish colonial rule (1779-95), through American acquisition (1795) and eventual statehood (established in 1817), and finally to slavery’s legal demise in 1865.

August 3, 2024

Interview with Katrina Anderson of the New Books Network

June 18, 2024

Invited talk at the Institute of Historical Research (IHR) Digital History Seminar, the University of London, “The Continuing Development of Generations of Freedom: The Natchez Database of Free People of Color, 1779-1865”

March 31, 2023

Ribianszky, Nik. “Generations of Freedom: The Natchez Database of Free People of Color, 1779-1865.” Journal of Slavery and Data Preservation 4, no. 1 (2023): 11-23

February 24, 2022

Black History Month Festival Author’s Book Talk Event hosted by the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH)

First 15 minutes below:

2022 BHM Festival Authors’ Book Signing – Feb 24th – YouTube

November 1, 2021:

Interview in The Author’s Corner on Current

The Author’s Corner with Nik Ribianszky – Current (currentpub.com)

October 14, 2021:

Article in The Conversation “How the Experience of Black People Freed From Slavery Set a Pattern for African Americans Today”

September 22, 2021

Author’s Book Talk Event at the 106th annual conference of the Association for the Study of African American History and Life (ASALH)

(8) ASALH Author’s Book Signing Dr Nik Ribianszky – YouTube

September 5, 2021

Interview with Barry Sheppard of History Now, Northern Visions Television (NVTV)

History Now: Gender, Movement and Violence in Natchez with Dr Nik Ribianszky on Vimeo

History Now can also be found on your favourite podcast app.