Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

(ca. 1793-?)

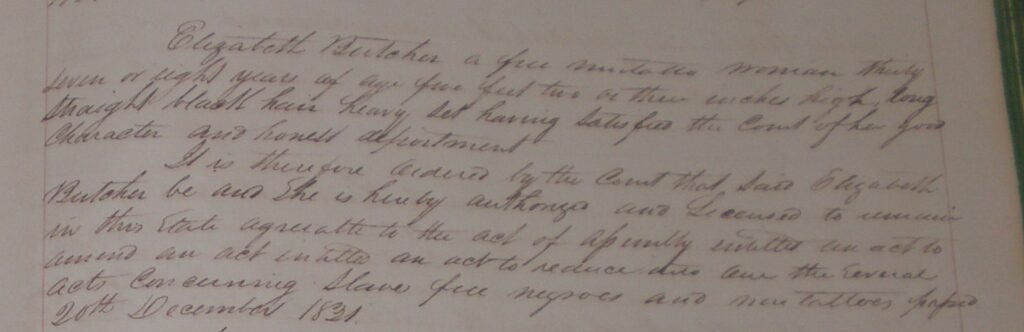

Free woman of color, property holder, and slave owner, Elizabeth Butcher resided in Natchez, Mississippi. Nothing is known about the early life of this woman and her status at the time of her birth, free or enslaved, as well as parentage is undetermined. But Elizabeth lived in Natchez for at least twenty years of her life and accrued property during that time due to a relationship with a white man, John Irby. She then came extremely close to losing it to another white man, Robert Wood, who attempted to wrest all of it from her by exploiting her vulnerability as a free woman of color.

In 1834, John Irby authored his last will and testament which clearly named Elizabeth as the administratrix of his estate consisting of the White House Tavern, surrounding land, buildings, two horses and buggy, household and kitchen furniture, all his money in the bank, and two slaves, Alexander and Creasy; in short, everything he had to give. Two years later, he added a codicil in which he acknowledged that he had sold Alexander and bought another slave, Eliza, and her three children, David, Nancy, and George. Elizabeth was to inherit a total of five slaves at his death. This legacy was a result of Elizabeth’s constant care of Irby as a nurse and housekeeper in his household for almost twenty years. John Irby unmistakably wished for his property to pass to her and to make arrangements for her to be provided for with this bequest.

Taken at face value, there is no indication that this was anything but a platonic association. It is possible that Irby rewarded Elizabeth out of gratitude for nursing and caring for him for almost two decades. He may have had no close family members or friends living to inherit his property. Or there is also the possibility that there may have been something not visible on the surface between the two. Regardless of the nature of the relationship by which she procured it, Elizabeth had to struggle through the courts to hold onto her inherited property. In 1839, Elizabeth was enmeshed in a legal battle with a white man, Robert Wood, for the right to be the administrator of the estate.

Woods, acting as the administrator of another estate, for the heirs of the deceased James Redman, petitioned the Adams County Probate Court to be granted the power of administration over the Irby estate. His primary claim was that there was a gambling debt that was incurred by Irby in his lifetime, which was due to the estate of James Redman. He charged that Elizabeth had not yet repaid it in her administration of the Irby estate. He was granted the powers of administration over the estate and seized four of the five slaves and was poised to sell them off. He was unable to complete this action due to some legal technicalities, but the Court granted him permission instead to try to sell the White House Tavern. Shortly thereafter, the Court authorized him to sell the five slaves. He advertised their sale, but Elizabeth petitioned the Court before they and the property were sold.

She charged that she had not been notified that her power of administration of Irby’s estate was being challenged, revoked from her, and reassigned to Wood. She had never formally revoked her letters of administration to the estate. Instead, Wood endeavored to acquire them without her knowledge and to dispose of the five slaves, the tavern, and the remainder of the estate, all of which he claimed added up to no more than $5,000, before she was able to act and protect her holdings. He was almost successful.

The court ordered Wood to defend himself, if possible, in why he should be permitted to retain his power of administration over Irby’s estate. Wood pulled out his last card and accused Elizabeth of being “a woman of color and as such is incapable of accepting or holding the office of Administratrix on Said Estate, under the Law of the Country (Robert W. Wood (Admins.) of John Irby vs. Elizabeth Butcher).” This point of the case is extremely crucial as Wood attempted to strike her Achilles’s heel by seeking to damage her credibility to hold the position as a woman of color. If Elizabeth resembled the great majority of Natchez free property-holding women of color, then doubtless, she was of mixed race. If it were not readily apparent to the court that she was of African ancestry, Wood may have felt this could have cost her the estate under the laws of Mississippi which required that free people of color hold property under a white sponsor. But Elizabeth’s answer exhibits her confidence in her claim to the estate as “she admits that she is a free woman of color but denied that she is thereby rendered incapable of accepting or holding the Office of Executrix upon the Estate of John Irby Deceased” (Robert W. Wood (Admins.) of John Irby vs. Elizabeth Butcher).

The Probate Court agreed with Elizabeth’s legitimacy as Administratrix and ultimately provided relief to her in this case. The judge ruled that Elizabeth had the right to retain her power of administration for the following reasons: no other administrator had been named in Irby’s will, the amount due Redman’s estate was misrepresented to the court, and further, Elizabeth had not been notified of Wood’s action as was her right. Woods went on to appeal the decision to the Mississippi High Court of Error and Appeals, but they upheld the lower court’s ruling and he was ordered to pay her court costs.

Elizabeth Butcher’s legal struggle was not an aberration with respect to the experiences of other free people of color. Whites frequently preyed upon people of African descent, free and enslaved, by contesting the wills of their friends or relatives who bequeathed property or freedom to African men and women. Elizabeth was fortunate in not having her fortune reversed in Wood’s appeal, but unfortunately, after this case, she becomes lost in the historical record and her activities remain enshrouded in mystery.

*From Nik Ribianszky’s entry on Butcher, Elizabeth inThe African American National Biography Project, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham eds. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

Further Reading

Robert W. Wood (Admins.) of John Irby vs. Elizabeth Butcher, Mississippi High Court of Error and Appeals, Case #679, (1841).

Links